Managing Panic

What is Panic? To understand panic, we need to understand fear.

You can think of fear as an automatic alarm response that switches on the moment there is danger. Think about what would happen to you if a dangerous animal approached you. For most people it would be panic stations! You, and almost everyone, would go through a whole series of bodily changes, like your pumping, breathing faster, sweating, all in order to respond to the danger in front of you. This alarm response would probably lead us to either run for our lives or become sufficiently ‘pumped up’ to physically defend ourselves. This alarm response is an important survival mechanism called the fight or flight response.

Sometimes, however, it is possible to have this intense fear response when there is no danger – it is a false alarm that seems to happen when you least expect it. It is like someone ringing the fire alarm when there is no fire! Essentially, a panic attack is a false alarm.

Many people experience some mild sensations when they feel anxious about something, but a panic attack is much more intense than usual. A panic attack is usually described a a sudden escalating surge of extreme fear. Some people portray the experience of panic as ‘sheer terror’. Let’s have a look at some of the symptoms of a panic attack:

-

-

- Skipping, racing or pounding heart

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

- Choking sensations

- Chest pain, pressure or discomfort

- Nausea, stomach problems or sudden diarrhea

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, feeling faint

- Tingling or numbness in parts of your body

- Hot flushes or chills

- Feeling things around you are strange, unreal, detached, unfamiliar, or feeling detached from body

- Thoughts of losing control or going crazy

- Fear of dying

-

As you can see from the list, many of the symptoms are similar to what you might experience if you were in a truly dangerous situation. A panic attack can be very frightening and yo may feel a strong desire to escape the situation. Many of the symptoms may appear to indicate some medical condition and some people seek emergency assistance.

-

-

- It peaks quickly – between 1 to 10 minutes

- The apex of the panic attack lasts for approximately 5 to 10 minutes (unless constantly rekindled)

- The initial attack is usually described as “coming out of the blue” and not consistently associated with a specific situation, although with time panics can become associated with specific situations

- The attack is not linked to marked physical exertion

- The attacks are recurrent over time

- During an attack the person experiences a strong urge to escape to safety.

-

Many people believe that they may faint whilst having a panic attack. This is highly unlikely because the physiological system producing a panic attack is the opposite of the one that produced fainting.

Sometimes people have panic attacks that occur during the night when they are sleeping. They wake from sleep in a state of panic. These can be very frightening because they occur without an obvious trigger.

Panic attacks in, and of themselves, are not a psychiatric condition. However, panic attacks constitute the key ingredient of Panic Disorder if the person experiences at least 4 symptoms of the list previously described, the attacks peak within about 10 minutes and the person has a persistent fear of having another attack.

Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Someone with panic disorder has a persistent fear of having another attack or worries about the consequences of the attack. Many people change their behaviour to try to prevent panic attacks. Some people are affected so much that they try to avoid any place where it might be difficult to get help or to escape from. When this avoidance is severe it is called Agoraphobia.

Panic Disorder is more common than you think. A recent study reported that 22.7% of people have reported experience with panic attacks in their lifetime.3.7% have experienced Panic Disorder and 1.1% have experienced Panic Disorder plus Agoraphobia. * These numbers equate to millions of people world wide. If left untreated, Panic Disorder may become accompanied by depression, other anxiety disorders, dependence on alcohol or drugs and may also lead to significant social and occupational impairment.

Biology and Psychology of Panic

Panic attacks (the key feature of Panic Disorder) can be seen as a blend of biological, emotional & psychological reactions. The emotional response is purely fear, the biological & psychological reactions are described in more detail below.

When there is real danger, or when we believe there is danger, our bodies go through a series of changes called the fight/flight response. Basically, our bodies are designed to physically respond when we believe a threat exists, in case we need to either run away, or stand and fight. Some of these changes are

-

-

- An increase in heart rate and strength of heart beat. This enables blood and oxygen to be pumped around the body faster.

- An increase in the rate and depth of breathing. This allows more oxygen to be taken into the body.

- An increase in sweating. This causes the body to become more slippery, making it harder for a predator to grab, and also cooling the body.

- Muscle tension in preparation for fight/flight. This results in subjective feelings of tension, sometimes resulting in aches and pains and trembling and shaking.

-

When we become anxious and afraid in situations where there is no real danger, our body sets off an automatic biological “alarm”. However, in this case it has set off a “false alarm”, because there is no danger to ‘fight’ or run from.

When we breathe in we take in oxygen that is used by the body, and we breathe out carbon dioxide. In order for the body to run efficiently, there needs to be a balance

between oxygen and carbon dioxide. When we are anxious, this balance is disrupted because we begin to overbreathe. When the body detects that there is an imbalance, it responds with a number of chemical changes. These changes produce symptoms

such as dizziness, light-headedness, confusion, breathlessness, blurred vision, increase in heart rate, numbness and tingling in the extremities, clammy hands

and muscle stiffness. For people with panic, these physiological sensations can be quite distressing, as they may be perceived as being a sign of an oncoming attack,

or something dangerous such as a heart attack. However these are largely related to overbreathing and not to physical problems.

We’ve described the physical symptoms of panic. People who panic are very good at noticing these symptoms. They constantly scan their bodies for these symptoms. This scanning for internal sensations becomes an automatic habit. Once they have noticed the symptoms they are often interpreted as signs of danger. This can result in people thinking that there is something wrong with them, that they must be going crazy or losing control or that they are going to die.

There are a number of types of thinking that often occur during panic, including:

-

-

- Catastrophic thoughts about normal or anxious physical sensations (eg “My heart skipped a beat – I must be having a heart attack!”)

- Over-estimating the chance that they will have a panic attack (eg “I’ll definitely have a panic attack if I catch the bus to work”)

- Over-estimating the cost of having a panic attack: thinking that the consequences of having a panic attack will be very serious or very negative.

-

We’ve described the physical symptoms of panic. People who panic are very good at noticing these symptoms. They constantly scan their bodies for these symptoms.

This scanning for internal sensations becomes an automatic habit. Once they have noticed the symptoms they are often interpreted as signs of danger. This can result in people thinking that there is something wrong with them, that they must be going crazy or losing control or that they are going to die.

There are a number of types of thinking that often occur during panic, including:

-

-

- Catastrophic thoughts about normal or anxious physical sensations (eg “My heart skipped a beat – I must be having a heart attack!”)

- Over-estimating the chance that they will have a panic attack (eg “I’ll definitely have a panic attack if I catch the bus to work”)

- Over-estimating the cost of having a panic attack: thinking that the consequences of having a panic attack will be very serious or very negative.

-

The Vicious Cycle of Anxiety

The essence of anxiety is worrying about some potential threat. It is trying to cope with a future event that you think will be negative. You do this by paying more attention to possible signs of potential threat, and looking internally to see whether you will be able to cope with that threat. When you notice your anxious symptoms, you think that you can’t cope with the situation, and therefore become more anxious. This is the start of the vicious cycle of anxiety.

If you feel anxious, or anticipate feeling anxious, it makes sense that you will do things to reduce your anxiety. People sometimes try and reduce the anxiety by avoiding the feared situation altogether. This avoidance instantly decreases the anxiety because you have not put yourself in a distressing situation. However, while avoidance makes anxiety better in the short term you have also made the anxiety worse in the long term.

An illustration of this is when you avoid going to a supermarket to do the shopping because that’s where you experience fear. As a result you successfully avoid the distress you associate with supermarkets. In the short term, you do not feel anxious. However in the long term you become even more unwilling to confront anxiety. You continue to believe that emotion is dangerous and should be avoided at all costs. You do not disconfirm your catastrophic predictions about what may happen in the shopping centre. You continue scanning your environment for signals of danger and signals of safety. In this way your anxiety may increase and generalise to other situations.

Vicious cycles play an important role in maintaining anxiety. However, you can turn this cycle around to create a positive cycle that will help you overcome anxiety. One important step in this cycle is gradually confronting feared situations. This will lead to an improved sense of confidence, which will help reduce your anxiety and allow

you to go into situations that are important to you.

Some people might encourage you to tackle your biggest fear first – to “jump in the deep end” and get it over and done with. However, many people prefer to take it “step by-step”. We call this “graded exposure”. You start with situations that are easier for you to handle, then work your way up to more challenging tasks. This allows you to build your confidence slowly, to use other skills you have learned, to get used to the situations, and to challenge your fears about each situational exposure exercise. By doing this in a structured and repeated way, you have a good chance of reducing your anxiety about those situations.

Reversing the Vicious Cycle of Anxiety

Vicious cycles play an important role in maintaining anxiety. However, you can turn this cycle around to create a positive cycle that will help you overcome anxiety. One important step in this cycle is gradually confronting feared situations. This will lead to an improved sense of confidence, which will help reduce your anxiety and allow

you to go into situations that are important to you.

Some people might encourage you to tackle your biggest fear first – to “jump in the deep end” and get it over and done with. However, many people prefer to take it “step by-step”. We call this “graded exposure”. You start with situations that are easier for you to handle, then work your way up to more challenging tasks. This allows you to build your confidence slowly, to use other skills you have learned, to get used to the situations, and to challenge your fears about each situational exposure exercise. By doing this in a structured and repeated way, you have a good chance of reducing your anxiety about those situations.

Breathing is an essential part of life, but did you know that breathing plays an essential role in anxiety? This information will briefly discuss the role of breathing in anxiety and guide you through a simple calming technique that uses breathing patterns to help you relax.

Breathing is a powerful determinant of physical state. When our breathing rate becomes elevated, a number of physiological changes begin to occur. Perhaps you’ve noticed this yourself when you‘ve had a fright; you might suddenly gasp, feel a little

breathless and a little light-headed, as well as feeling some tingling sensations around your body. Believe it or not, the way we breathe is a major factor in producing these and other sensations that are noticeable when we are anxious.

You might already know that we breathe in oxygen – which is used by the body – and we breathe out carbon dioxide. In order for the body to run efficiently, there needs to be a balance between oxygen and carbon dioxide, and this balance is maintained through how fast and how deeply we breathe. Of course, the body needs different amounts of oxygen depending on our level of activity. When we exercise, there is an increase in both oxygen and carbon dioxide; in relaxation there is a decrease in both oxygen and carbon dioxide. In both cases the balance is maintained.

When we are anxious though, this balance is disrupted. Essentially, we take in more oxygen than the body needs – in other words we overbreathe, or hyperventilate. When this imbalance is detected, the body responds with a number of chemical changes that produce symptoms such as dizziness, light-headedness, confusion, breathlessness, blurred vision, increase in heart rate to pump more blood around, numbness and tingling in the extremities, cold clammy hands and muscle stiffness.

The normal rate of breathing is 10-12 breaths per minute – what’s your breathing rate?

While overbreathing and hyperventilation are not specifically dangerous (it’s even used in medical testing!), continued overbreathing can leave you feeling exhausted or “on edge” so that you’re more likely to respond to stressful situations with intense anxiety and panic.

Gaining control over your breathing involves both slowing your rate of breathing and changing your breathing style. Use the calming technique by following these steps

and you’ll be on your way to developing a better breathing habit.

1. Ensure that you are sitting on a comfortable chair or laying on a bed

2. Take a breath in for 4 seconds (through the nose if possible

3. Hold the breath for 2 seconds

4. Release the breath taking 6 seconds (through the nose if possible)., then pause slightly before breathing in again.

5. Practice, practice, practice!

-

-

- When you first begin changing your breathing, it may be difficult to slow your breathing down to this rate. You may wish to try using a 3-in, 1- hold, 4-out breathing rate to start off with.

- When you are doing your breathing exercises, make sure that you are using a stomach breathing style rather than a chest breathing style. You can check this by placing one hand on your stomach and one hand on your chest. The hand on your stomach should rise when you breathe in.

- Try to practice at least once or twice a day at a time when you can relax, relatively free from distraction. This will help to develop a more relaxed breathing habit. The key to progress really is practice, so try to set aside some time each day.

-

By using the calming technique, you can slow your breathing down and reduce your general level anxiety. With enough practice, it can even help to reduce your anxiety when you are in an anxious situation.

Relaxation

Muscle tension

Muscle tension is commonly associated with stress, anxiety and fear as part of a process that helps our bodies prepare for potentially dangerous situations. Even though some of those situations may not actually be dangerous, our bodies respond in the same way. Sometimes we don’t even notice how our muscles become tense, but perhaps you clench your teeth slightly so your jaw feels tight, or maybe your shoulders become. Muscle tension can also be associated with backaches and tension headaches.

Progressive Muscle Relaxation

One method of reducing muscle tension that people have found helpful is through a technique called Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR). In progressive muscle relaxation exercises, you tense up particular muscles and then relax them, and then you practice this technique consistently.

When you are beginning to practice progressive muscle relaxation exercises keep in mind the following points.

-

-

- Physical injuries. If you have any injuries, or a history of physical problems that may cause muscle pain, always consult your doctor before you start.

- Select your surroundings. Minimise the distraction to your five senses. Such as turning off the TV and radio, and using soft lighting.

- Make yourself comfortable. Use a chair that comfortably seats your body, including your head. Wear loose clothing, and take off your shoes.

- Internal mechanics. Avoid practicing after big, heavy meals, and do not practice after consuming any intoxicants, such as alcohol.

-

Relax ok!

Once you’ve set aside the time and place for relaxation, slow down your breathing and give yourself permission to relax.

When you are ready to begin, tense the muscle group described. Make sure you can feel the tension, but not so much that you feel a great deal of pain. Keep the muscle tensed for approximately 5 seconds. Relax the muscles and keep it relaxed for approximately 10 seconds. It may be helpful to say something like “Relax” as you relax the muscle. When you have finished the relaxation procedure, remain seated for a few moments allowing yourself to become alert.

1. Right hand and forearm. Make a fist with your right hand.

2. Right upper arm. Bring your right forearm up to your shoulder to “make a muscle”.

3. Left hand and forearm.

4. Left upper arm.

5. Forehead. Raise your eyebrows as high as they will go, as though you were surprised by something.

6. Eyes and cheeks. Squeeze your eyes tight shut.

7. Mouth and jaw. Open your mouth as wide as you can, as you might when you‘re yawning.

8. Neck. !!! Be careful as you tense these muscles. Face forward and then pull your head back slowly, as though

you are looking up to the ceiling.

9. Shoulders. Tense the muscles in your shoulders as you bring your shoulders up towards your ears.

10. Shoulder blades/Back. Push your shoulder blades back, trying to almost touch them together, so that your chest is pushed forward.

11. Chest and stomach. Breathe in deeply, filling up your lungs and chest with air.

12. Hips and buttocks. Squeeze your buttock muscles

13. Right upper leg. Tighten your right thigh.

14. Right lower leg. !!! Do this slowly and carefully to avoid cramps. Pull your toes towards you to stretch the calf muscle.

15. Right foot. Curl your toes downwards.

16. Left upper leg. Repeat as for right upper leg.

17. Left lower leg. Repeat as for right lower leg.

18. Left foot. Repeat as for right foot.

Practice means progress. Only through practice can you become more aware of your muscles, how they respond with tension, and how you can relax them. Training your body to respond differently to stress is like any training – practising consistently is the key.

Behavioural Experiments for Negative Predictions

Negative Predictions

Many people who suffer from anxiety, depression or low self-esteem tend to make negative predictions about how certain situations will turn out.

You may tend to

Overestimate the likelihood that bad things will happen or that something will go wrong

Exaggerate how bad things will be

Underestimate your ability to deal with things if they don’t go well

Ignore other factors in the situation which suggest that things will not be as bad as you are predicting

When you jump to such negative conclusions about the future, you will tend to engage in unhelpful behaviours such as

Avoid the situation totally

Try the situation out but escape when things seem too difficult

Be overly cautious and engage in safety behaviours

The problem with these strategies is that they prevent you from actually testing out your predictions. This makes it very hard for you to ever have a different experience from what you expected, so you continue to expect the worst.

For example, let us imagine you have been invited to a BBQ and your negative prediction is

“I will have a terrible time, no-one will speak to me, I will feel like a total fool.”

Your usual response may be to either avoid the BBQ altogether, or to attend but to leave as soon as you feel uncomfortable, or to stand in the corner and speak only to one person you already know. This may help you reduce your discomfort in the short term, but it also contributes to the continuation of your negative predictions, and this means continuation of anxieties.

Testing Our Predictions

What could have been an alternative way to handle the BBQ situation described above?

A different approach could be to go to the BBQ, try your best to have a nice time and speak to others, and use the resulting experience as evidence to test your original negative prediction. Think of yourself as a scientist, putting your thoughts under the microscope to examine the evidence for and against your thoughts, instead of assuming that all of your negative predictions are true. Behavioural experiments are a good way for testing these predictions. Next we will go through the steps, using the BBQ situation as an example.

1.Be clear about the purpose of the experiment – the point is to test out your negative predictions and help you to develop more realistic and/or balanced predictions.

2. What is the thought or belief that you are trying to test? Rate how strongly you believe this prediction (0-100)

I will have a terrible time at the BBQ. Even if I try to talk to people, no-one will talk to me. (90)

3. What is an alternative prediction or belief? Rate how strongly you believe this alternative (0-100)

I will find at least one person to talk to and will have an ok time. (10)

4. Design the actual experiment – what will you do to test your prediction, when will you do it, how long will it take, and with whom? Try to be as specific as possible. There are no boundaries to how creative you can be, and it is ok to ask for help.

I will go to the BBQ at 8pm, alone, and will stay for at least one hour. I will try to make conversation with at least three people, one that I did not know already. I will only drink one glass of wine.

5.Make sure you set your experiment at an appropriate level. It is best to start simply and

increase the challenge step-by-step. Identify likely problems and how to deal with them.

There might not be anyone I know at the BBQ. But I will at least know the host and I can ask to be introduced to some other people.

1. Carry out the experiment as planned. Remember to take notice of your thoughts, feelings, and behaviours.

2. Write down what happened, what did you observe? Consider the evidence for and against your original prediction. What did this say about your negative prediction

I felt quite nervous at first and wanted to leave. I used

breathing to calm myself. The host was friendly and seemed

happy to talk to me, and I also spoke to Kelly, who I hadn’t

seen in some time. Kelly introduced me to her partner Jim

and we had a good chat about travel. At one point I worried

I had said something stupid, but Jim didn’t seem to notice so

my worry passed.

3. What have you learned?

I am capable of making conversation and enjoying myself in a casual social situation.

4. Rate how strongly you now believe in your original prediction and the alternative (0-100)

I will have a terrible time at the BBQ. Even if I try to talk to

people, no-one will talk to me. (10)

I will find at least one person to talk to and will have an ok

time. (80)

One of the ways that people avoid feeling anxiety in certain situations is to avoid those situations

wherever possible. However, by not exposing yourself to those situations you don’t get the chance to

disconfirm your fears, which in turn can make those fears even stronger. If being in those situations is important to you, you will need to face your fears in a real situation and begin to turn social activity into a positive experience. This information sheet is designed to show you how you can begin to do that.

Some people might encourage you to tackle your biggest fear first – to “jump in the deep end” and get it over and done with. However, many people prefer to take it “step by- step”, what some people call “graded exposure”. By using graded exposure you start with situations that are easier for you to handle, then work your way up to more challenging tasks. This allows you to build your confidence slowly, to use other skills you have learned, to get used to the situations, and to challenge your fears about each situational exposure exercise. By doing this in a structured and repeated way, you have a good chance of reducing your anxiety about those situations.

The first thing to do is to think about the situations that you fear and try to avoid. For example, some people might fear and avoid going to social places, or being assertive with others. Make a list of these situations.

Once you have made the list, indicate how much distress you feel in those situations by giving them each a rating on a scale of 0 to 100.

0 – You are perfectly relaxed

25-49 – Mild: You can still cope with the situation

50-64 – Moderate: You are distracted by the anxiety, but are still aware of what’s happening

65-84 – High: Difficult to concentrate, thinking about how to escape

85-100 – Extreme: The anxiety is overwhelming and you just want to escape from the situation

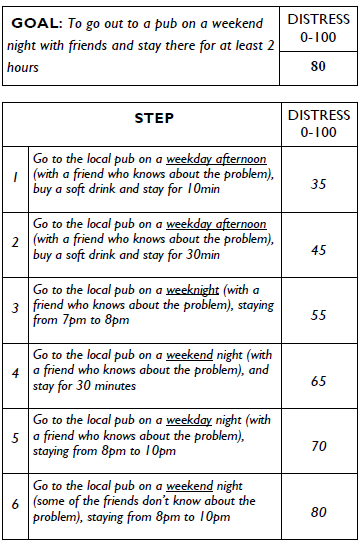

Now you can start to turn the situations you avoid into goals that you’d like to achieve. For example, a situation that you avoid might be “Going to pubs“, which has a distress rating of 75. A goal for this might be “To go out to a pub on a weekend night with friends and stay there for at least 2 hours”.

When you are developing a goal, it helps to make them

SMART:

Specific: It needs to be as clear (eg compare “To eat in public”

with “To eat lunch in a local restaurant on my own.”

Measurable: It needs to be easily assessed (eg compare

“Being friendly” with “Staying for 2 hrs” – what does

‘friendly’ mean?)

Achievable: It needs to be possible and probable to achieve

Relevant: It needs to be important to you

Timebound: It needs to have an end date for completion

Now that you have a personal, realistic, achievable, measurable, and specific goal that you’d like to achieve, you can plan your “graded exposure” program. This involves breaking the goal down so that

you can work step-by-step towards your major goal. Of course, goals with high distress (eg a rating of 80+) will need more steps than a medium distress goal (eg a rating of 40+). You can break your

goal into smaller steps by changing WHO is there, WHAT you do, WHEN you do it, WHERE you do it, and HOW long you do it for. Follow the SMART criteria for developing each step. Here’s an example.

Recognising the Physical Symptoms of Panic

Panic Maintained

Some of the factors that are an important part of why panic is maintained are:

Thinking styles, such as catastrophic thinking. Panic sensations are interpreted as signalling something terrible, such as a medical emergency.

Focus on bodily sensations. Monitoring your body for symptoms of panic means that you are especially sensitive to the sensations, even when those changes are normal.

Avoidance. As a result of this fear of experiencing a panic attack, you avoid certain situations and sensations similar to panic.

It does seem natural to try to avoid the sensations that are similar to panic attacks. It might also seem natural to scan for the possibility of physical alarms, as this might help you to avoid them. However, if you don’t experience these sensations, you won’t give yourself any real evidence about one important thing: Panic sensations are not harmful.

Only by facing your “fears” about panic attacks and related physiological sensations will you have enough evidence to challenge your beliefs about physical alarms. One way to do this is to experience the physical sensations that you are afraid of, or “exposure to internal sensations”.

Exposure to Internal Sensations

Exposure helps by providing you with evidence that panic attacks are not harmful. It works by challenging three factors to break the cycle of panic and anxiety

Thinking styles. Through physiological sensations exposure, you will have direct evidence that such sensations are not catastrophic.

Focus on bodily sensations. If you do notice normal changes in your physiological sensations, exposure tasks will give you direct evidence that physiological sensations are not catastrophic, and this will reduce your fear of them. Further, if you are not afraid of these sensations, then there will be less reason to monitor your body for them.

Avoidance. Exposing yourself to physiological sensations is incompatible with avoiding them. By repeatedly exposing yourself to such sensations, you will become used to them and you will be less likely to react with anxiety when you notice these sensations. By doing it over and over again, it becomes easier to do.

Preparing for Internal Exposure

Before you start, it is important to consider two things

You must be in a healthy physical state before completing these exercises. If you have health issues that might be complicated by physical strain, you should not continue. Check the list of physiological exercises to your doctor to determine whether you can proceed.

If you are finding the tasks particularly difficult, or are concerned about progress, please see a mental health practitioner who can guide you through the process.

Tasks to Try Out

With a stopwatch, try each of these tasks, designed to produce particular physiological sensations:

-

-

- Hyperventilation Breathe deeply & quickly through the mouth using as much force as you can for 1 minute

- Shaking head. Shake your head from side to side while keeping your eyes open. Be careful with your

neck. After 30 seconds, look straight ahead. - Head between legs. While sitting in a chair, place your head between your legs. After 30 seconds, stand upright quickly.

- Running in place/run up steps. Run/Step up and down quickly, maintaining a quick pace

- Maintain muscle tension. While sitting in a chair tense/tighten all of your muscles for 1 min

- Hold your breath. Take a deep breath and hold it for 30 sec or as long as you can

- Spinning. Use a swivel chair to spin around as quickly as possible for 1 min

- Breathe through a straw. Use a narrow straw to breathe, whilst holding your nose closed, for 1 min

- Chest breathing. Take a deep breath until your chest is “puffed up”, then take short, sharp breaths, breathing just from your chest

- Stare at a spot. Stare at spot on a blank wall, or at a mirror, without shifting your gaze, for 1.5 min

-

Remember

-

-

- Try not to stop the task early, use distraction, or avoid doing the task properly

- Pay attention to physical sensations that occur during the exercise as well as those which occur shortly after

- Dispute unhelpful thoughts during the exercise

- Use thought diaries, social support, and scheduling to maximise your continued commitment to working through the exposure exercises.

-